Message Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT) has been relevant for years. It’s enjoying even wider attention now thanks to the explosive growth of IoT, with both consumer and industrial economies deploying distributed networks, edge computing, and data-emitting devices as part of everyday operations. This means lightweight, open-source and accessible protocols will only become more important with time. The article below provides a conceptual deep-dive into MQTT, how it works, and its uses now and in the future.

A bit of background

MQTT is a publish-subscribe messaging protocol dating back to 1999, when IBM’s Andy Stanford-Clark and Cirrus Link’s Arlen Nipper published the first iteration. They envisioned MQTT as a way to maintain machine-to-machine communication on networks with limited bandwidth or unpredictable connectivity. One of its first use cases was to help keep sections of oil pipeline in contact with one another and with central sites using satellites.

As a result of the rugged conditions that inspired it, the protocol is lightweight and boasts a limited code footprint. This makes it ideal for low-power devices and those with limited battery lives, including now-ubiquitous smartphones and ever-growing numbers of sensors and connected devices.

As such MQTT has become the go-to protocol for streaming data between devices with limited CPU power and/or battery life, and for networks with expensive or low bandwidth, unpredictable stability or high latency. Which is why MQTT is known as the ideal transport for IoT. MQTT is built on the TCP/IP protocol, but there is an offshoot, called MQTT-SN, which is designed for use on Bluetooth, UDP, ZigBee and other non-TCP/IP IoT networks.

MQTT isn’t the only publish-subscribe (pub/sub) realtime messaging protocol of its kind, but it has already achieved widespread adoption in a variety of surroundings that depend on machine-to-machine communication. Its contemporaries include Web Application Messaging Protocol, Streaming Text-Oriented Messaging Protocol, and Alternative Message Queueing Protocol.

For developers who want to build applications with robust functionality and wide compatibility with internet-connected devices and apps, including browsers, smartphones and IoT devices, MQTT is a logical choice.

How MQTT works – the basics

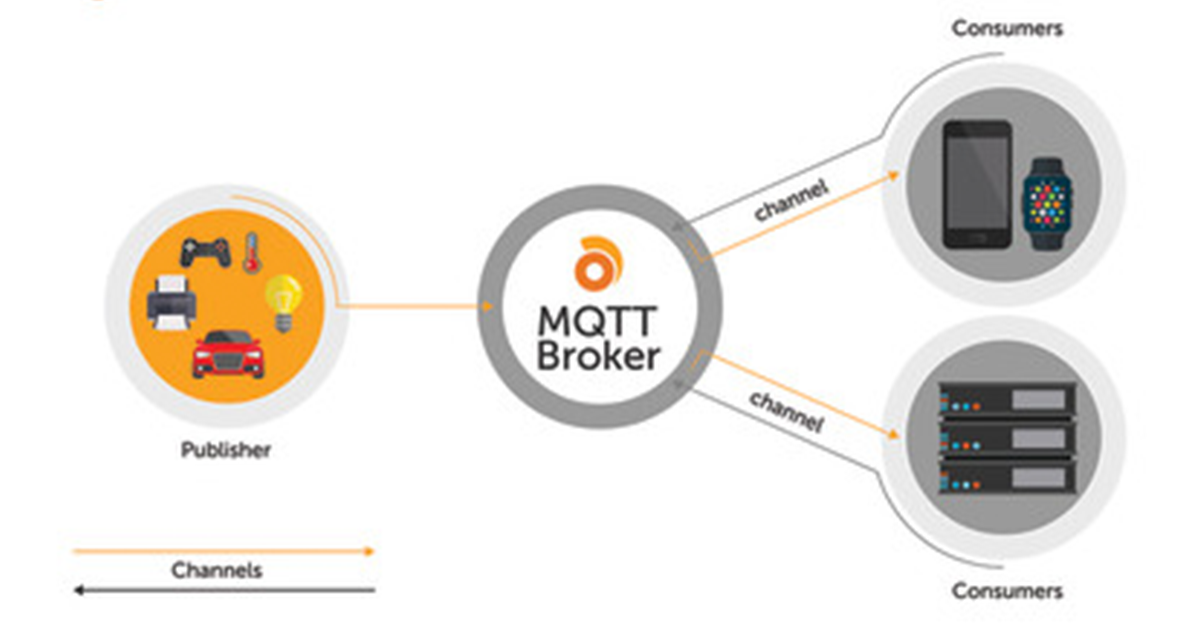

A communication system built on MQTT consists of the publishing server, a broker and one or more clients. The publisher does not require any configuration concerning the number or location of subscribers receiving messages. Likewise, subscribers do not need publisher-specific setup. There may be more than one broker on the system distributing messages.

MQTT broker

MQTT provides a way to create a communication channel hierarchy — sort of like a branch with leaves. Whenever a publisher has new data to distribute to clients, the message is accompanied by a delivery control note. Higher-level clients may receive every message, while lower-level clients may receive those relating to just one or two of the basic channel ‘leaves’ at the bottom of the delivery hierarchy. These can facilitate the exchange of information as small as two bytes or as large as 256 megabytes.

An example of how you might configure an MQTT client to connect through an MQTT broker:

var options = {

keepalive: 60,

username: 'xVLyHw.YA9fyg',

password: 'yU4BEnHoxMf7Svne',

port: 8883

};

var client = mqtt.connect('mqtts:mqtt.ably.io', options);Any data published through or received by an MQTT broker will be binary encoded as MQTT is a binary protocol. This means that you’ll need to interpret the message to get the original contents out. Here’s how it looks using Ably and JavaScript:

var ably = new Ably.Realtime('xVLyHw.YA9fyg:yU4BEnHoxMf7Svne');

var decoder = new TextDecoder();

var channel = ably.channels.get('input');

channel.subscribe(function(message) {

var command = decoder.decode(message.data);

});MQTT brokers may sometimes accumulate messages related to channels that have no current subscribers. If that’s the case, messages will either be discarded or retained, depending on instructions in the control message. This is useful at times when new subscribers may require the most recent recorded data point, instead of being forced to wait until the next dispatch.

Notably, MQTT uses plain text to transmit security credentials and does not otherwise provide support for authentication or security functionality. That’s where the SSL framework comes in, helping protect transmitted information from being intercepted or otherwise tampered with.

You can also use Ably token-based auth with MQTT, if you want to avoid your API key being disclosed to the actual MQTT client at all. (If you are using MQTT without SSL, then token auth is mandatory, to prevent API keys being transmitted over cleartext). An example of token auth with MQTT:

var options = {

keepalive: 60,

username: INSERT_TOKEN_HERE,

password: '',

port: 8883

};

var client = mqtt.connect('mqtts:mqtt.ably.io', options);

client.subscribe("[mqtt]tokenevents", {

/* Create a new token called 'NEW_TOKEN' */

client.end();

options.username = NEW_TOKEN;

client = mqtt.connect('mqtts:mqtt.ably.io', options);

});MQTT functionality – a deeper dive

According to IBM, MQTT is:

Agnostic with respect to the content of the message

Ideal for one-to-many communication distribution and decoupled applications

Equipped with a “last will and testament” feature to notify parties of abnormal client disconnection

Dependent on TCP/IP for basic connectivity purposes

Designed for at most once, at least once and exactly once message delivery

To use MQTT, one can assume the role of publisher, consumer, or both at once.

One of the distinguishing characteristics of MQTT is its leverage of channels. Other protocols utilize this in their own ways, but MQTT is unique in treating each one as a file path – like so:

channel = "user/path/channel"Channels ensure that each listener receives the messages intended for them. MQTT accomplishes all kinds of useful communication functionality by treating channels as a file path, including allowing message filtration based on where — or at which level or branch — listeners subscribe to on the file path.

Understanding MQTT messaging format

Here’s a look at the two components that comprise each message exchanged using the MQTT protocol:

Byte 1: Contains the message type (client request to connect, subscribe acknowledgment, ping request, etc.), a duplication flag, retain instructions for messages and information on the quality of service level (QoS).

Byte 2: Contains information on the remaining length of the message, including the payload and any data in the optional variable header.

The QoS flag in Byte 1 is worth special consideration, since it lies at the heart of the variable functionality that MQTT supports. QoS flags contain the following values based on the intent and urgency of the message:

0 = at most once = server fires and forgets — messages may be lost or duplicated

1 = at least once = recipient acknowledges delivery — messages may be duplicated, but delivery is assured

2 = exactly once = server ensures delivery — messages arrived precisely once without loss or duplication

Now, let’s look at the ways different QoS levels affect how MQTT can be used in IoT devices and other applications.

When might you use MQTT?

As IoT applications have found ways to disrupt industries on a huge scale, MQTT has come into focus as an open, straightforward and scalable way to roll out distributed computing and IoT functionality to a wider user base — in both the consumer and industrial markets.

As laid out above, MQTT is a lightweight messaging protocol built for questionable network quality and batteries with physical limitations, including power source and CPU. However, that doesn’t mean potentially lousy transmissions are its only application. From recurring data sampling to industrial machine control, MQTT delivers variable levels of service for a number of IoT infrastructure types:

Ambient sensor data

As mentioned, MQTT supports the “at most once” message delivery model. On networks with spotty coverage or high latency, this means information could be lost or duplicated. In fields where remote sensors record and transmit data at set intervals, this is a non-issue, since new readings are streaming in on a regular basis. Sensors in remote environments are usually low-power devices, making MQTT an ideal fit for IoT sensor buildouts with lower-priority data transmission needs.

Machine health data

In the interest of responding to emerging issues quickly and avoiding downtime, a wind turbine may require guaranteed delivery of machine health data to local teams even before that information hits a datacenter. For times like these, “at least once” message delivery ensures maintenance flags are seen by the right eyes at the right time to prevent problems, even if those flags may arrive as duplicates. This is for higher-priority machine-to-machine communication systems.

Billing systems

There are even higher-priority and higher-fidelity messages that require the right touch. In business situations where duplicated data entries are not OK, including where billing is involved, the QoS tag comes in handy. This eliminates duplicate or lost message packets across billing or invoicing systems and cuts down on anomalies and unnecessary strife with clients.

When shouldn’t you use MQTT?

Developers have a choice of protocols for designing and deploying bi-directional IoT functionality, including MQTT, HTTP, CoAP, WebSockets (where CPU/battery permits) and others. Whether MQTT is the best choice depends on what you want your application to do and the nature of your hardware.

Being designed for extremely low-bandwidth environments, MQTT can be rather inflexible in its quest to save every byte. For example, the spec defines five error responses with which a server can reject a connection (such as bad username or password, or unacceptable protocol version); if the server wants to indicate some error that is not one of those five, it’s out of luck. Worse, if an error occurs once the connection is running, there is no mechanism for an error protocol message at all; the server can only shrug and abruptly terminate the TCP connection, leaving the client with no idea why it was dropped (and without any way to distinguish a deliberate disconnection from a transient network issue). For people used to more flexible and easier to debug (albeit less bandwidth-conserving) pubsub protocols, such a miserly approach to bandwidth can be a little primitive.

MQTT is often referenced alongside HTTP, which is why Google mounted a study comparing the two for response time, data transmission size and other attributes of importance to developers. MQTT came out on top in Google’s tests but only when the connection can be reused to send multiple payloads.

HTTP and MQTT are both good choices for IoT applications because of their reasonably compact transmission sizes and their low strain on device battery life and memory.

CoAP is another protocol frequently compared to MQTT for IoT developments. The two are similar but come with notable differences. MQTT is a many-to-many protocol, whereas CoAP is mostly a one-to-one protocol for communications between a server and a client. CoAP also provides metadata, discovery and content negotiation features, which MQTT does not have.

In cases where clients need only to receive data, Server-Sent Events is also a valid choice.

How to quickly get set up with MQTT

The MQTT GitHub repo has an extensive list of open source MQTT libraries across various languages. Below are two examples of getting set up with an open source MQTT broker and JavaScript and .NET library.

Eclipse Mosquitto – an open source MQTT broker

Eclipse Mosquitto is an open source (EPL/EDL licensed) message broker that implements the MQTT protocol versions 5.0, 3.1.1 and 3.1. Mosquitto is lightweight and is suitable for use on all devices from low power single board computers to full servers.

MQTT.js

MQTT.js is a client library for the MQTT protocol, written in JavaScript for node.js and the browser. Here’s an example of sending a message using MQTT.js:

var mqtt = require('mqtt')

var client = mqtt.connect('mqtt://test.mosquitto.org')

client.on('connect', function () {

client.subscribe('presence', function (err) {

if (!err) {

client.publish('presence', 'Hello mqtt')

}

})

})

client.on('message', function (topic, message) {

// message is Buffer

console.log(message.toString())

client.end()

})MQTTnet

MQTTnet is a high performance .NET library for MQTT based communication. It provides a MQTT client and a MQTT server (broker).

Set up an MQTT client:

// Create a new MQTT client.

var factory = new MqttFactory();

var mqttClient = factory.CreateMqttClient();After setting up the MQTT client options a connection can be established. The following code shows how to connect with a server:

// Use WebSocket connection.

var options = new MqttClientOptionsBuilder()

.WithWebSocketServer("broker.hivemq.com:8000/mqtt")

.Build();

await client.ConnectAsync(options);Consume incoming messages:

client.UseApplicationMessageReceivedHandler(e =>

{

Console.WriteLine("### RECEIVED APPLICATION MESSAGE ###");

Console.WriteLine($"+ Topic = {e.ApplicationMessage.Topic}");

Console.WriteLine($"+ Payload = {Encoding.UTF8.GetString(e.ApplicationMessage.Payload)}");

Console.WriteLine($"+ QoS = {e.ApplicationMessage.QualityOfServiceLevel}");

Console.WriteLine($"+ Retain = {e.ApplicationMessage.Retain}");

Console.WriteLine();

Task.Run(() => client.PublishAsync("hello/world"));

});Publish a message:

var message = new MqttApplicationMessageBuilder()

.WithTopic("MyTopic")

.WithPayload("Hello World")

.WithExactlyOnceQoS()

.WithRetainFlag()

.Build();

await client.PublishAsync(message);Check out the MQTTnet docs and wiki for more examples.

Service providers at the enterprise level have MQTT-ready servers available that support scalable messaging between mobile applications, industrial machines and a wide variety of other IoT use cases. Check out this tutorial to learn about using MQTT through an enterprise-ready broker.

What about deploying MQTT at scale?

There are two considerations when it comes to MQTT and scale: is it the right protocol and, regardless of protocol choice, the infrastructure and network capabilities needed to handle increased device-to-device streaming over MQTT.

Lightweight Machine-to-Machine (LWM2M) is another protocol to consider alongside MQTT at the enterprise level. Compared with MQTT, LWM2M is sometimes better suited for longer-term IoT deployments. MQTT is ideal when companies want to engage in a trial run of IoT functionality without a lot of buy-in, whereas LWM2M provides features for companies building longer-term infrastructure that’s versatile. LWM2M also provides superior device management tools, such as connectivity monitoring, firmware updates and remote device actions. For enterprises with lots of un-managed devices sending high volumes of data to a central IoT platform, LWM2M is the better choice. However, we’re talking huge-scale IoT deployments so most of the time MQTT is a more than adequate choice. Plus, of the two, MQTT remains more common with wider support.

Then there’s infrastructure capabilities. The number of concurrent connections a server can handle is rarely the bottleneck when it comes to server load. Most decent MQTT servers/brokers can support thousands of concurrent connections, but what’s the workload required to process and respond to messages once the MQTT server process has handled receipt of the actual data? Typically there will be all kinds of potential concerns, such as reading and writing to and from a database, integration with a server, allocation and management of resources for each client, and so on. As soon as one machine is unable to cope with the workload, you’ll need to start adding additional servers, which means now you’ll need to start thinking about load-balancing, synchronization of messages among clients connected to different servers, generalized access to client state irrespective of connection lifespan or the specific server that the client is connected to – the list goes on and on.

Such concerns are deserving of an article all of their own, and you’ll find plenty in the Engineering section of the Ably blog – see in particular a write-up on some of the complexities of operating realtime messaging infrastructure at scale.

Where does MQTT stand today?

In April 2019, OASIS officially released version 5.0 of MQTT as an official open-source standard. OASIS is a nonprofit consortium consisting of 600 member organizations and 5,000 individual participants.

Version 5.0 introduces several new features that should be of interest to realtime developers. These new features are backwards-compatible with current versions of MQTT already in deployment.

Those new features include:

Improved reporting for errors: Return codes can now inform users when data isn’t transmitting successfully for whatever reason. Reason strings are supported, but optional, and help improve diagnostics and troubleshooting efforts.

Subscription sharing: To help balance the load, subscriptions can be shared across multiple clients on the receiving end.

Message properties: Version 5.0 introduces metadata as a part of the message header. It can convey additional information to the end-user or it may facilitate some of the other features included below.

Channel alias: Publishers can replace channels with numerical identifiers to cut down on how many bytes require transmission.

Message expiration: Messages can be tagged for automatic deletion if the system cannot deliver them within a preset amount of time.

The full list of new functionality MQTT 5.0 can be found in Appendix C of the official standard.

In addition to the panoply of consumer-level devices and services on the market today, MQTT has found a home in enterprise infrastructure of all shapes and sizes. This includes smartphones and tablets, energy-monitoring systems, medical devices, oil rigs and drilling sites, the automotive and aerospace industries, and sensors and machine vision systems used in material handling, construction, supply chain, retail, and more.

MQTT and Ably

MQTT is a popular, widely-supported, and relatively mature protocol. It’s great for an array of realtime uses, not just IoT deployments. Yet as realtime data production and consumption continues to grow exponentially, MQTT won’t always be the right choice of protocol to fulfill your streaming needs. Keep an eye out on Ably’s Realtime Concepts section for information on other protocols and how they fit in with your use case.

Ably provides an MQTT broker / protocol adapter that’s able to translate back and forth between Ably’s own protocol, allowing for seamless integration with any existing systems and connections. With support for WebSockets, HTTP, SSE, STOMP, AMQP, and many more, Ably provides an interoperable, globally-distributed realtime messaging infrastructure layer. With over 40 Client Library SDKs and support for proprietary realtime protocols, getting set up or migrated over to Ably is simple.

Recommended Articles

WebSocket reliability in realtime infrastructure

How reliable are WebSockets, and what does it take to build a reliable WebSocket infrastructure? We'll explore this and the considerations to make on whether to use a PaaS.

Socket.IO vs SockJS

Compare realtime libraries Socket.IO and SockJS on performance, scalability, developer experience, and features.

Scaling realtime web apps with JavaScript and WebSockets

Learn how to build dependable realtime web apps that scale with JavaScript and WebSockets.